The Loom

We weave our scarves on a wooden loom, a simple equipment for weaving.

As true as that is, our loom's simplicity is in fact a gross understatement; as simple as it is, our loom is the result of at least five millennia of evolution of a tool that supplied a basic human necessity, clothing; and furnished rich and famous with fabric for their resplendent regalia.

This machine now might be an anachronism and perhaps be even commercially unviable, but we cannot exaggerate its importance: it embodies human ingenuity of invention and ability to leverage basic tools to find solutions to problems. To understand the problem our humble loom solved, we need to understand weaving.

Weaving is one of the several methods to create fabric, a supple material, by interlacing threads. The interlacing can be done either by single element techniques: such as looping, netting, knitting, crocheting; or multiple element techniques: knotting, coiling, twining, braiding, weaving. All these methods of making fabric continue to be used; but weaving is the most common: it proved to be the most efficient.

Weaving entails interlacing two sets of threads rectangularly; the process comprises three operations: keeping one set of thread taut (warp); opening the warp; and inserting and beating up another set of thread (weft) across the opened warp. The way the warp and weft interlace defines the weave: plain, basket, twill, satin. Evolution of looms has been finding techniques, through either process or physical construction, to do these three things better - and faster, when it came to attaining economies of scale.

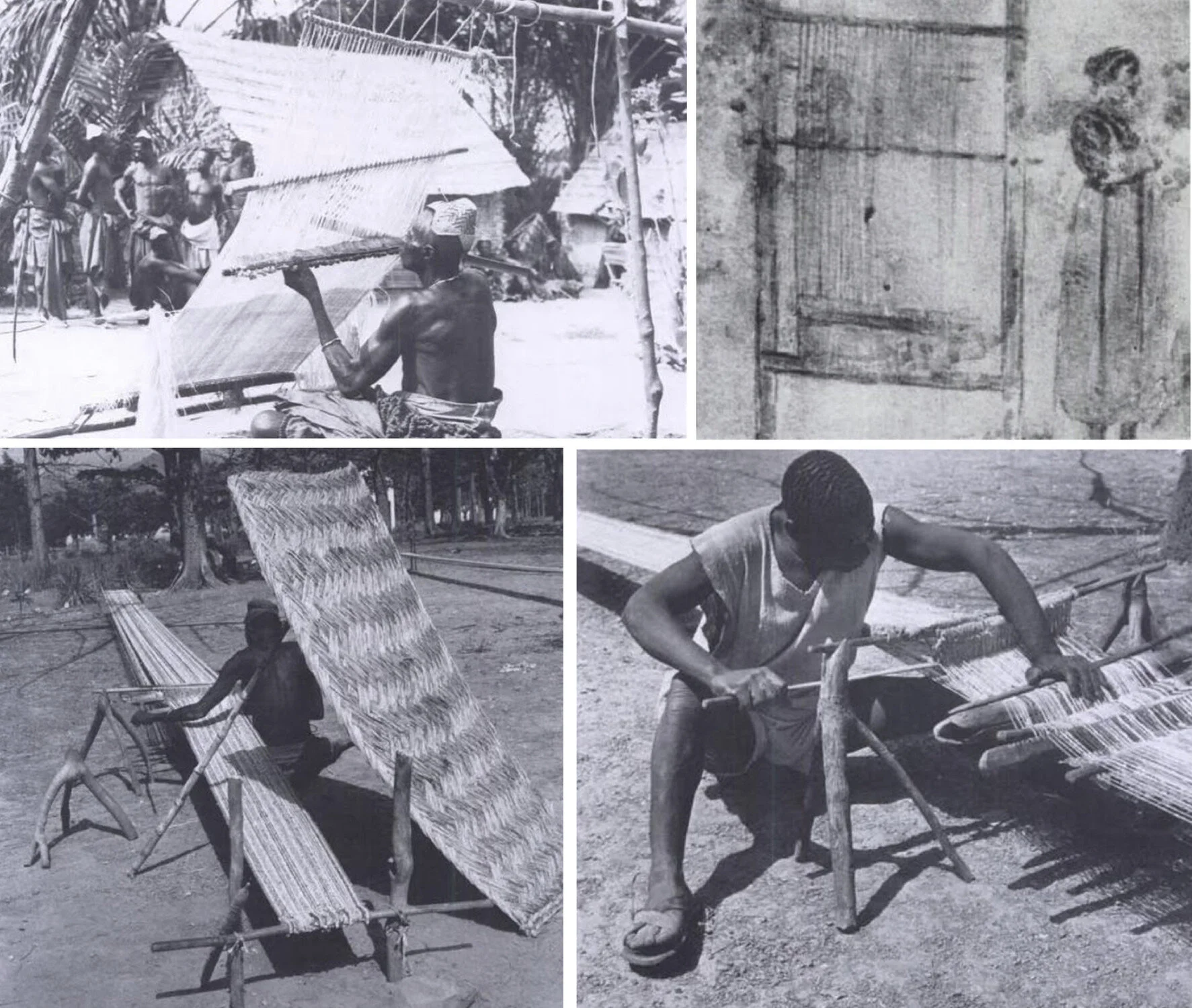

It all started, nobody knows exactly when, with warp-weight loom where the tension to keep the warp taut was achieved by hanging the threads from a bar (even a tree branch) and attaching some weight down. This kind of loom was used in ancient Greece and later by the Native American tribes in North Pacific.

Finding means to provide tension to keep warp stretched, and mechanisms to slacken it, contributed to the evolution of loom's design and structure. The loom's development continued from warp-weight to a two-bar loom, which the early Egyptians used. In another case, warp tension was achieved by attaching a bar (with one end of threads tied to it) to a belt around weaver's waist. This loom, back-strap loom, made possible, among others, fabulous Andean textiles. It can still be found in use in remote regions of Asia and several parts of Central and South America.

In fact, most of these prehistoric looms continue to be used, by one community or the other, in some part of the world. For example, not far from our facility in Bhagalpur, we came across a most primitive loom - we saw only its disassembled parts, a few pieces of wood really - used to weave a coarse rug made of wool from local sheep.

The second step: opening the warp; was at first, naturally, done by hand; and then with a stick that released the yarn wound onto it, as it was pushed across the warp. For several centuries, this process could be improved only marginally until the invention of flying shuttle in the early 18th century. This simple boat-like gadget traverses the opened warp, inserting the weft yarn wound on a pirn lying inside it. The flying shuttle sped up weaving; and allowed weavers to make wider fabric.

The allied step of raising and selecting the warp, to insert the weft and make the required pattern, has also undergone significant changes: from using a shed-rod carrying raised warp to another ingenious device, heddle, a looped wire with an eye in the centre through which a warp yarn was passed. To create patterns and designs, required sections of warp were selected using shafts or harnesses that attached the heddles with foot treadles.

The"final" third step in the weaving process, beating, or battening, of weft was earlier done by a weaver's sword of wood (batten knives) which gave way to reed, a comblike tool, that, together with the heddle, combined warp spacing and beating of weft. The reed is suspended from the loom's framework and swings to press the weft against the woven fabric.

For the sake of simplicity and narrative, we have not talked about plenty of other looms, such as drawloom or jacquard loom (that allowed complex floral patterns using perforated cards). Their shape and mechanics have been essentially captured by the above description of evolution of looms. Furthermore, all the looms fundamentally either improved efficiency or provided tools to ease the effort on one or more of the three steps of the weaving process. In fact, even the most modern machines -- such as the rapier loom, which uses a finger-like carriers, called rapiers, to carry weft -- use the same basic operational principles of weaving that has been used by their precursors since prehistoric times.

The evolution of loom was also necessitated by use of new fibres, such as silk and cotton; and driven too by expansive creativity and human imagination to create patterns and to express oneself.

Many societies across geographies came up with their own ingenious tools to aid weavers in the three basic steps of the weaving process: this explains the existence of myriads of looms and the rich history of weaving.

We see reflections of this rich history in our own loom. Technically, it is a flying shuttle treadle-loom, with possibility of 32 treadles or pedals, which allow us to create complex geometrical patterns; but we keep our designs simple and everlasting and instead focus on quality of weave and softness and texture of the fabric.

We are aware of the various possibilities enabled by modern handlooms still being made in Europe; but we are frugal and rooted in our geography. We acknowledge: it was challenging to get these looms made locally in the quality we wanted; but we are happy with the result.

Our looms are made of wood from sal tree: a native of the Indian subcontinent with religious significance to Hindus and Buddhists. The channel in the loom -- that allows the flying shuttle to traverse the width of the loom -- is made with teak for smoothness.

We have been told these looms age and acquire their own character. We are looking forward to that...